Property from the Jay T. Snider Collection of Benjamin Franklin

Washington, George | An extraordinary letter marking the conjunction of three of the most consequential figures of the American Revolution: George Washington, the Marquis de Lafayette, and Benjamin Franklin

Auction Closed

January 27, 03:32 PM GMT

Estimate

1,000,000 - 1,500,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

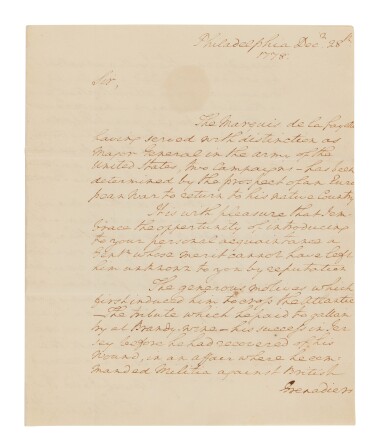

Washington, George

Autograph letter signed (“Go: Washington”) as commander of the Continental Army, 2 pages (241 x 198 mm) on the first leaf of a bifolium of laid paper (watermarked Posthorn | GR), Philadelphia, 28 December 1778, to Benjamin Franklin; faint seal stain, central vertical crease neatly reinforced. Accompanied by the original full-sheet address wrapper (343 x 255 mm; watermarked Dove and Olive Branch | WMT) directed in a clerical hand to “The Honble. | Benjamin Franklin Esqr | Minister Plenipotentiary of the United States | Versailles,” clerical file docket (“General Washingtons”), fragment of red wax seal; worn with loss and repair at fold creases. Please note: the unusual separate address leaf has preserved the letter in remarkably fresh condition. Morocco folding-case gilt, chemises, by Papuchyan H & H Bindery.

You May Also Like