Property from the Collection of Elsie and Philip Sang

Lincoln, Abraham | The President thanks a schoolboy on behalf of "all the children of the nation for his efforts to ensure "that this war shall be successful, and the Union be maintained and perpetuated."

Auction Closed

January 27, 03:32 PM GMT

Estimate

200,000 - 300,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

Lincoln, Abraham

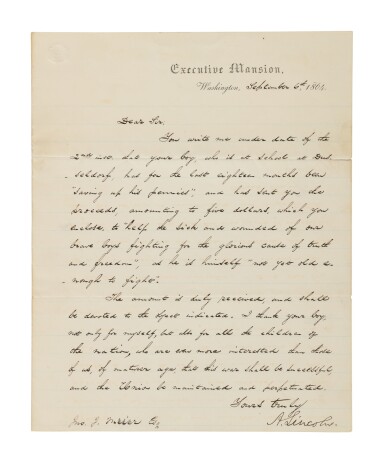

Manuscript letter signed ("A. Lincoln") as sixteenth President, one page (250 x 200 mm) on a bifolium of blue-ruled Executive Mansion letterhead, Washington, D.C., 6 September 1864, to John J. Muir of Brooklyn, thanking Muir's son for his contribution to the Union cause, body of the letter in the hand of presidential secretary Edward D. Neill, docketed on the verso, "To Mothers brother."

You May Also Like

![Le Livre [et le Second Livre] de la Jungle. 1919. Précieuse reliure Art Déco historiée de Marius Michel, enrichie d'un bois gravé de Shmied sur le premier plat. Exemplaire hors commerce de tête sur vélin d'Arches, complet de ses 130 compositions de Jouve.](https://dam.sothebys.com/dam/image/lot/6906d825-d050-4c4a-9aba-44d690e84c74/primary/extra_small)