Property from the Collection of Dr. Robert Small

Mosby, John Singleton | Three letters to his wife, 1861–1862, taking him from Bull Run to officer rank

Lot closes

December 16, 03:39 PM GMT

Estimate

20,000 - 30,000 USD

Starting Bid

14,000 USD

We may charge or debit your saved payment method subject to the terms set out in our Conditions of Business for Buyers.

Read more.Lot Details

Description

Mosby, John Singleton

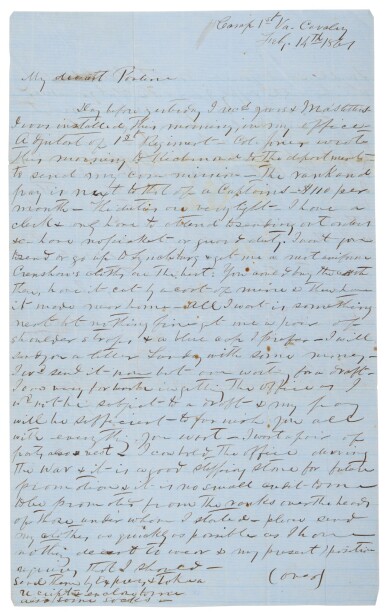

Series of 3 autograph letters signed ("John S. Mosby"; "Jno. S. Mosby") to his wife Pauline: (1) 3 pages (317 x 200 mm) on a bifolium of blue-ruled blue paper, in pencil, "Camp Vigilance Berkley Co.," 12 July 1861; top quarter of third page lost, fold separations artlessly repaired with transparent tape; (2) 2 pages (303 x 187 mm) on a sheet of blue-ruled blue paper, "Camp [near Gainesville, Virginia] 1st Va. Cavalry, 14 February 1861 [but 1862]; lightly discolored on verso; (3) 1 page (303 x 187 mm) on a sheet of blue-ruled blue paper), "Camp Stonewall Jackson [near Gainesville, Virignia]," 18 February 1862; small loss to upper right corner costing 3 characters of address, lower fold separation artlessly repaired with transparent tape.

A remarkable series of letters from Mosby to his wife, tracing the early military development of the feared Ranger from his first action at Bull Run through his promotion to officer rank.

The First Virginia Cavalry was composed of twelve pre-war militia companies. During the 1860–1861 "secession winter," John Singleton Mosby, a lawyer in Bristol, Virginia, was, like his home state, strongly drawn to remaining in the Union. But when the Old Dominion seceded in April, Mosby enlisted in the company commanded by Captain William "Grumble" Jones. In this first letter of three to his wife, the private soldier who would become known as the "Gray Ghost" demonstrates the aptitude for scouting and observation that would serve him so well during his guerilla campaigns as he describes the situation nine days before First Bull Run: the first major battle of the Civil War.

"I received your last letter … at Gordonsville. We reached Winchester last Monday—only stayed there one night & we were ordered here to join Col. Stuarts regiment of Cavalry. … We are about 12 miles from … Genl Jonstons headquarters) & about 7 or 8 from Martinsburg where Genl. Patterson is encamped with about 35000 federal forces—we can hear the yankees drumbeats. I saw George in Winchester—he looks very well. He stayed all night with me at my camp—he wants to join our company. I will now relate my first adventure with the Yankees yesterday. Capt. Jones took 50 of his Company out on a scouting expedition—we went down towards Martinsburg, when in two miles of there we flushed a party of Yankees. They broke & took into a corn field. The main body of the party took up the road after them & the Capt sent five men (including myself) around to intercept them—for a mile we went at breakneck speed … we then wheeled—rode up to two who immediately surrendered—we sent them on back & four of us them pursued the others in to Martinsburg—we drove in three infantry & about fifteen of their cavalry—and ride up to a within half mile of their encampment & had a full view of it. We then rode back to the main body of our party—about this time we had surrounded another of them when one of our men came galloping up & said that we were cut off by about 250 yankee cavalry—of course we didn't stop to catch a prisoner but commenced preparing for a fight—but it turned out to be another Company from our own regiment—we scoured about the woods & fields fully two hours in full view of their tents & they didn't dare to come out and attack us—we divided the accoutrements of the two prisoners with the squad that took them. I got one of their canteens—the finest I ever saw—made of zinc which will keep water cool much longer than tin."

This brief respite, Mosby continues, was disturbed by "the firing at an engagement between another company of our regiment (from Rockingham) & a yankee foraging party. They dispersed them & killed one & took a horse—'nobody hurt' on our side—our men were very eager for the fray & I believe would have dashed into their camp if Capt. Jones would have let them." His prisoners, Mosby reports, "were New Yorkers—one a corporal. They had just been into an old lady's house and robbed her of all her preserves. Stuart's regiment is a perfect terror to them."

Mosby looks ahead to another skirmish—and to an eventual larger engagement. "We will go out on another expedition this week. It is impossible to conjecture where a battle will come off. Genl Johnstons offered them battle … but they will not accept." (Mosby here interrupts his own narrative to report the passing of a funeral cortege for a Confederate soldier who had accidently shot and killed himself. He then continues:) "They are fortified at Martinsburg—Johnston has about 15000 men only." Not knowing when a battle might ensue, Mosby and his cohorts are in a perpetual state of readiness: "We sleep every night with our arms on—keep our horses bridled & saddled ready to start at a moments warning."

The letter closes on a more mundane note, asking for news from home, telling of the "great treat" of a gift of two gallons of buttermilk from a civilian, and apologizing for the somewhat sloppy hand of the letter, "I am writing on a piece of plank in the hot sun which might well be a sufficient apology for such a letter."

At the time of the second letter in the series, Mosby was out of the hot sun in winter camp at Gainesville. He had been promoted, but he seems to have lost a bit of his appetite for soldiering, as this letter shows much more concern with his attire than with the potential campaigns of the new year.

"Day before yesterday I recd. Yours & Ma's letters. I was installed this morning, in my office—Adjutant [ranking as lieutenant] of the 1st Regiment. Col. Jones wrote this morning to Richmond to the Department to send my commission.—The rank and pay is next to that of a Captains—$110 per month. The duties are very light, I have a clerk & only have to attend to sending out orders &c—have no picket or guard duty. I want you to send or go up to Lynchburg & get me a neat uniform. Crenshaw's cloths are the best. You could buy the cloth there and have it cut by a coat of mine & then have it made near home. All I want is something neat but nothing fine get me a pair of shoulder straps & a blue cap I prefer. I will send you a letter Sunday with some money."

After mentioning some other perquisites of being Adjutant to Pauline, Mosby abruptly returns to the subject of his uniform: "I want a pair of pants also & vest. I can hold the office during the War & it is a good stepping stone for future promotions & it is no small credit to me to be promoted from the ranks over the heads of those under whom I started—please send my clothes as quickly as possible as I have nothing decent to wear & my present position requires that I should. Send them by Express & take a receipt & enclose to me also some socks." This letter, early in his separation from Pauline, concludes by expressing Mosby's hope for an eventual family reunion: "I want you to come here with the children as I must see you all. When I was a private I could not go off without leave but now that I am an officer I have more privileges. I would not desire you to come just now as you wd. have to stay six or seven miles from camp & the roads are in such a condition that you wd. be almost as far off as now—love to all and kiss my babes for me."

Mosby was able to affect his longed-for reunion more quickly that perhaps he anticipated. In the final letter of this series, written just four days after the second, Mosby tells Pauline of the arrangements he made. "I drop you a line to enclose you a draft for $150—instead of returning to Bristol 1st March I want you to come over here—that is, provided I can get a place for you all to stay a few weeks. Capt. Rambo (our quartermaster) told me yesterday that he thought I could board you at the place where his wife & a good many officers wifes are boarding—it is about six miles from here. I will see about it this week at all events."

Mosby then turns his attention, once more, to the uniform that Pauline is ordering for him. "You must put Va. buttons on the coat you have made for me. I also want a vest of the same cut to button straight up to the chin—put some yellow braid on the collar. I also want my pair of black pants if you brought them with you—please have my clothes made as soon as possible as I am in need of them."

In concluding this letter, Mosby turns to the vital battle being contested at Fort Donelson, Tennessee. "We are suffering the most intense anxiety to hear the final result from Donelson—if we are defeated there it will prolong the war I fear—but the idea of giving up or abandoning the field now should never enter a Southern man's head—to be sure there must be a costly sacrifice of our best blood—but the coward dies a thousand deaths—the brave man dies but one—the first Cavalry is almost unanimous for the war." Unbeknowst to Mosby, Ulysses S. Grant had taken Fort Donelson two days earlier, and the Civil War was destined to be prolonged far beyond the optimistic parameters that Mosby—and many others, both North and South—had anticipated.

War-date letters by Mosby are scarce on the market.

You May Also Like